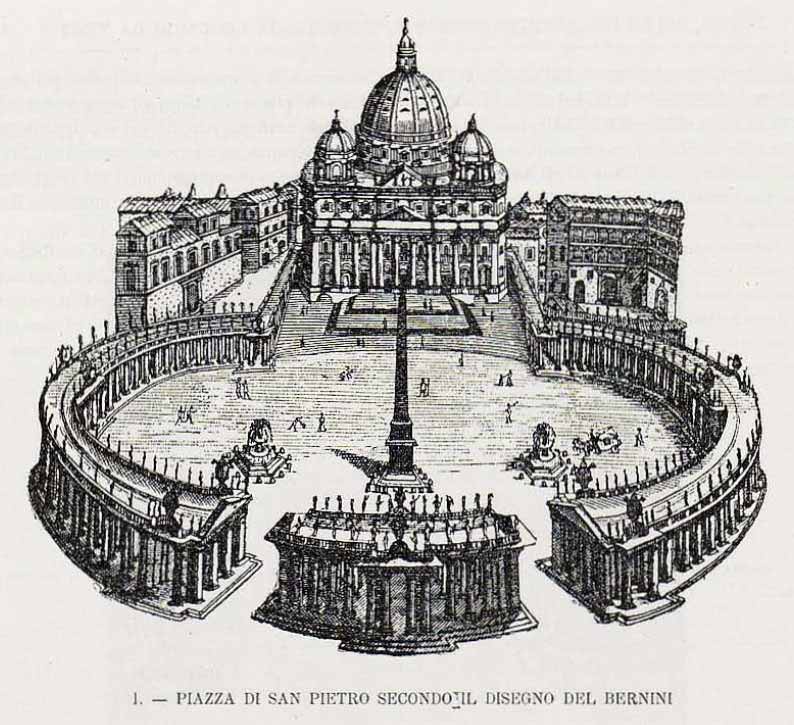

St. Peter's Square and the basilica behind it occupy a small valley located between the Vatican hill and the Janiculum hill occupied in classical times by the Circus of Nero, via Cornelia and a cemetery area now called the Vatican Necropolis, where it was placed, according to tradition, the tomb of St. Peter after his martyrdom in the nearby Circus. For this reason the great Constantinian basilica was erected on this area in the fourth century.

With this construction a vast esplanade called platea Sancti Petri was created, also burying the cemetery area, partly occupied by the church, partly by the four-sided portico and partly left free.

On its edge in the Middle Ages, the Borgo district was born which occupied the area between the Tiber and the esplanade.

Pope Pius II had a marble staircase built in front of the facade of the basilica and started a loggia for the blessings of Francesco del Borgo. Pope Nicholas V had planned to transform the shapeless earthen space of the stalls into a porticoed square within the overall reorganization of the Vatican area in which Bernardo Rossellino was engaged, at the same time regularizing the three medieval streets of the Borgo that belonged to it. The project did not follow immediately.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century the square (platea Sancti Petri) was roughly rectangular, without paving, with a difference in height of about ten meters between the foot of the staircase that led to the basilica and the opposite district of the Borgo that reached the Tiber.

During the whole of the sixteenth century the square was not affected by the reconstruction works of the basilica which continued to turn the old facade, the four-sided portico and the various leaning buildings towards the square. Pius IV in the mid-sixteenth century widens the square on both sides. In 1586 Sixtus V had the ancient Egyptian obelisk transported in front of the basilica, about halfway between the foot of the ancient staircase and the block opposite, which, after being used as a goal in the Neronian Circus, rose, not far from the building, on the southern side of the Basilica. Archaeological excavations have shown how the obelisk, before the move organized by Domenico Fontana, had maintained its original position of the first century.

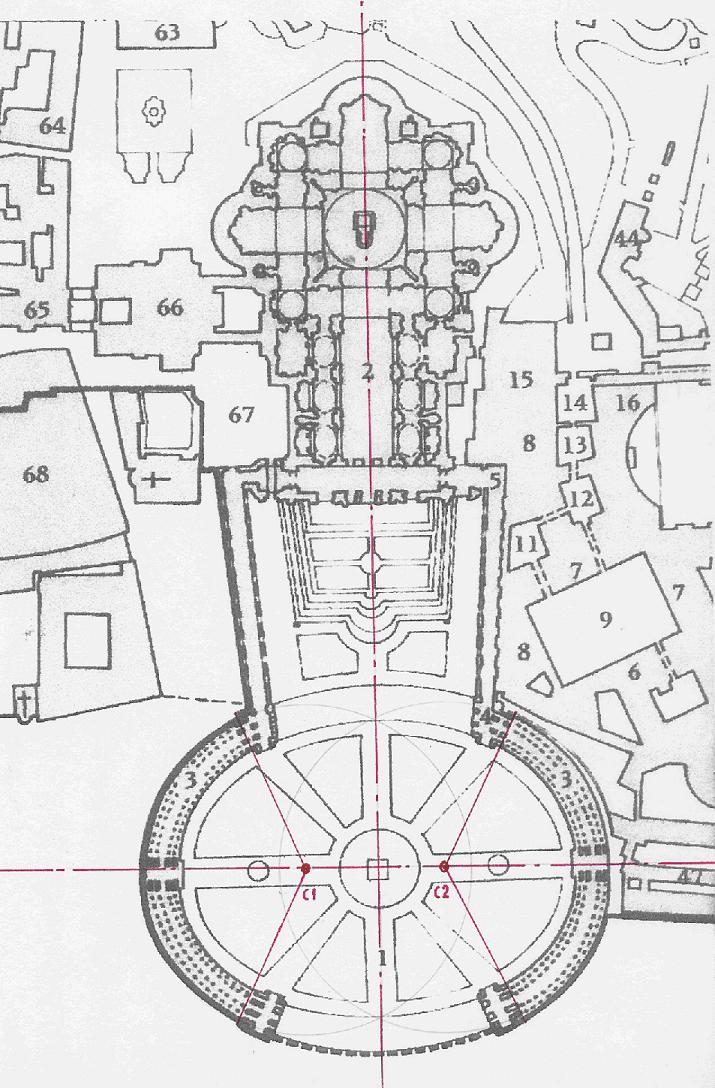

However, when, twenty years later, the new factory of San Pietro stands at the end of the square, the obelisk is displaced by 1.56 meters to the north with respect to its axis, because the architect Domenico Fontana, in transporting and placing it, he had probably referred to the Constantinian basilica then partially still standing. Moreover, if it had been placed on the axis of the new building, it would have been almost close to the blocks south of the square, whose demolition will be decided much later.

It is only from the seventeenth century that the question of the square arises. In fact, Pope Paul V, in the first decades of the century, had the longitudinal body of the church built by Maderno, definitively renouncing Michelangelo's central plan project.

It is in this situation that we move from the age-old questions relating to the planimetric layout of the church, to the questions relating to its facade and the definition of the space in front.

The problem was that of transforming a fairly undifferentiated space, such as the Sancti Petri platea, into a monumental and representative space, directly functional to the basilica. While, to build the nave, the ancient four-sided portico of Paradise was destroyed, the problem of satisfying its functions as an antechamber of St. Peter arises again, but further on, more externally to the east.

Furthermore, now the popes look from the Quirinal to St. Peter's in a formal and ideological perspective different from the one they had from the Vatican. San Pietro ceases to be the grandiose chapel of the papal palace and returns to be one of the basilicas of Rome, and indeed the troubled project, which Julius II and Bramante had initiated, of making the church the symbolic center of Christianity is now taking place.

The square, in the following years, was always wanted and thought of as closed also for evident contrast to the previous Sancti Petri stalls, very open in every direction. However, the seventeenth-century intervention actually includes three successive parts: the longitudinal nave with its facade; the internal St. Peter's Square, "closed" and jointly designed; the external piazza Rusticucci, "open", void obtained without any design or "project".

The architectural and urban axis

What in the city is the main axis (via Alessandrina), in the square becomes the secondary axis, all the more so since the demolition of the Ferrabosco tower which marked the entrance to the Vatican Palaces, in correspondence with this urban axis.

Inevitably Bernini for the first time in the history of the square imposes the axis of the basilica; but he keeps inside the centuries-old axis of the Borgo Nuovo, even if completely hidden.

He does not underline it in any way, neither the design of the pavement, nor any sculptural eminence; but it is true that nothing interrupts it, and the fountain in the northern exedra of the square is tangent to the external corner of this path, precisely in order not to intercept it.

However, having to accept the obelisk as the center of the new square, Bernini had to rotate the major axis of the oval to make it parallel to the facade, thus imparting a significant deformation to the trapezoidal part.

St. Peter's Square - Virtual Tour 360°

Address: Piazza San Pietro, Città del Vaticano

Phone: 06 0608

Site:

www.vaticanstate.vaLocation inserted by

CHO.earth