On the basis of what we read in the Iliad, in which a Mesthle, son of Pilemene king of the Aenets is mentioned, some scholars of the past have proposed a legendary origin for the city by reconnecting to the events of the hero Antenore, progenitor of the Venetians. These, escaped from destroyed Troy, after a long wandering by sea found refuge in the region that he himself called Veneto where he founded the city of Padua. Following him there was also Mesthle who instead settled with others in a wood in front of the Lagoon, the so-called Selva Fetontea, founding a fortified city which, from his name, he called Mestre.

Legends aside, also due to the scarcity of finds and information regarding the ancient age, the origin of Mestre still remains obscure. As for the toponym, the most accredited hypothesis, proposed by Dante Olivieri, makes it derive from the Roman personnel Mester and Mestrius, documented especially in northern Italy; Filiasi remains vague and asserts that the etymology is Etruscan; Agnoletti, on the other hand, underlines the possible presence of the mad- root, referring to a marshy locality; those who want to reconnect with the myth, on the other hand, identify a similarity with names of oriental origin (Phrygian and Greek in particular).

But even in this case, as in countless others, it is in fact a name with a very simple origin, therefore far from legendary or mythological hypotheses; that is, just as the nearby Musestre, an ancient suburb of Roncade in the Treviso area, takes its name from the homonymous river that crosses it, Mestre acquired its name from Mestre or rather Mestria, a river on whose banks the village had risen in ancient times and that we went to unload where the Grand Canal of Venice now begins: From the Port of Olivolo or Lito the so-called Mestre or Marzenego river flowed through the canal of S. Secondo, and then into Canal Regio, meeting later at the confluence with the Canal Grande, the so-called Riva di Biagio today, the Bottenigo or Butinicus, into which Muson and Luxor, Pianca, Tergola and the Oriago river introduced, which for some time also bore the name of Brenta.

To these waters was added a branch of the Prealto for 'bucca de flumine' (now Lizza-Fusina) and joined with the Visignone, it formed the Giudecca canal, which was then enlarged in the 14th century by the Lenzina and the Vico canal; and all these branches were those that made up the Port of S. Niccolò di Lito (Antonio Luigi de 'Romanò, Prospectus on the consequences of the Venice lagoon, the ports and the neighboring provinces after the diversion of the rivers etc. pp. 47– 48. T. I. Venice, 1815). According to others, the original name of the river - and therefore also of the village - was instead Mestria: ... long before the 14th century a herd of the greater Medoaco, later called Brenta, which with Retrone passed near Padua, detached itself at the site of the today's Fiesso (Flexus) where it took the name of river Una or Prealto [...] when this flock arrived in the vicinity of Lizza Fusina it flowed into the lagoon [...] at the site where the church of San Geremia now stands, it happened to swell a portion of the waters of 'rivers Mestria or Marzinicus, Butinicus, Muxon, Tergala and Pionca ... ("On the destination of an ancient mural discovered in Venice. Conjectures by M. Eff. Ing. Giovanni Casoni." 'I.R. Veneto Institute of Sciences, Letters and Arts etc. "Pp. 220-221. Vol. VI. Venice, 1856).

And that the city was originally called Mestria, the still existing toponymic surnames 'Mestria' and 'de Mestria' seem to prove it, while those of 'Mestre' or 'de Mestre' do not exist in Italy (Guglielmo Peirce, "Prehistoric origins of Italian onomastics ". pp. 122–123. Smashwords, 2010). Of course, the question now remains as to why the river was called that way. As far as the foundation of the city is concerned, it seems that neither in the Paleoveneta nor Roman epochs there were any particularly important settlements in the area. The Itinerarium Burdigalense, a 4th century guide for pilgrims, mentioned only one "mutatio ad nonum" in the area, that is "a post office for changing horses located nine miles" (about 13.5km) from the city of Altino , along the Via Annia.

However, it seems possible the existence of a castrum, a small fortified center embryo of the medieval Castelvecchio. In this historical period the most frequent ecosystem was that of the oak-carpione forest. Furthermore, the area was swampy so much that the roads of Roman origin, which are built in a straight line up to Mira, were sinuous downstream to adapt to the territory. The oldest document bearing the name of Mestre, officially known, is the deed of donation with which in the year 994 Otto III, who later became Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in two years, intends to thank him for the services rendered his trusted leader Rambaldo belonging to the family of the Counts of Collalto up, those of the Susegana Castle (TV).

This was undoubtedly an important recognition since the forest of Montello, property in Treviso and 24 "mansi" (large extensions of arable land), including one "inter Mester et Paureliano et Brentulo", or between Mestre, and the Gazzera (Parlan and Brendole). The document remained in the hands of the Collaltos until 1917 when the castle was destroyed during the First World War. Among the ruins, there was probably quartered a unit of Bohemian soldiers, subjects of Vienna, who after the defeat found themselves having to return, mostly on foot to their places of origin.

One of them had the good idea of ??reinforcing his battered boots with that strange parchment found in the rubble. The document, therefore so miserably arrived in the Czech Republic, was first deposited, together with other stolen objects, in the local municipal archive, without anyone realizing the extraordinary historical value of the document. Only later did the person in charge of the Rokycany archive, located near Pilsen, to whom the document reached, understand its historical importance and emphasize it; today the diploma of Ottone III is the oldest document on parchment in the Czech Republic. A copy of the parchment was delivered to the municipality of Mestre-Carpenedo for its affixing inside the Municipality of Via Palazzo, also known as Ca ' Collalto.

Mestre could also be mentioned for the first time in a document dated 710 concerning donations to the monastery of San Teonisto di Casier. In this case, however, the document mentions a "Mestrina near the mountains" rather uncertain definition. It then appears in the aforementioned diploma of Emperor Otto III, who gave Rambaldo, count of Treviso, land in the area. The area was at this time become a borderland between the Holy Roman Empire and the Duchy of Venice, a place of passage for men and goods to and from nearby Venice. In fact, through the port of Cavergnago, located on the lower course of the flumen de Mestre, goods and men headed for the Lagoon passed through customs; moreover, three important connecting arteries with the hinterland passed through here: the Padovana (today's Miranese), the Castellana and the Terraglio (which connects Mestre to Treviso).

In 1152, in fact, the bull in which the bishop of Treviso Bonifacio, Pope Eugene III, recognized as lord of Mestre, specified among the properties a port, the castle and the archpriest church of San Lorenzo. The episcopal power, however, was threatened in the thirteenth century by the bullying of Ezzelino III da Romano. In 1237 his soldiers pushed into the territory of Mestre, devastating it, so much so as to force the nuns of the Monastery of San Cipriano, which stood nearby, to flee under the protection of Venice. Between 1245 and 1250 Ezzelino occupied the castle of Mestre in contrast with his brother Alberico, who became mayor of Treviso, until an agreement was reached between the two brothers: in 1257 the bishop Adalberto III Ricco was forced to give up the possession of the village and the castle to the civil administration of Treviso, who began to appoint you a captain for the exercise of administrative, military and judicial power. In 1274 a fire seriously damaged the Castelvecchio.

In 1317 Cangrande della Scala began to threaten Treviso, which, among other things, reinforced the castle of Mestre as a countermeasure. In 1318 the Scaligers tried several times to conquer the stronghold, which however resisted against all expectations. The soldiers, withdrawing, plundered the surrounding territories causing a serious economic crisis. Eventually, in 1323 Treviso, exhausted by the long war, capitulated and ended up under the Veronese dominion - and with it Mestre.

With the conquest of Padua and Treviso, the Scaligeri lordship began to constitute a serious threat to Venetian independence, together with the imposition of other powerful lordships, not only in Veneto, but also in Lombardy. At this point it became fundamental for Venice to take control of its hinterland. The Mestre Castle was one of the first objectives, being snatched from the Veronese on 29 September 1337 (day of San Michele Arcangelo), when it was conquered without a shot being shot by the Venetian commander Andrea Morosini, bribing the 400 German mercenaries on guard. In short, Venice took control of the entire Treviso area. The village of Mestre and the surrounding area was since then governed by a rector with the title of Podestà and Capitanio: the first was Francesco Bon. In 1405 there was also the dedication of Verona: in less than a century the Serenissima had therefore constituted its own Stato da Tera.

At this time the traffic of goods between Mestre and Venice had become so important that it required the construction of an artificial canal

, the Canal Salso, which from the lagoon reached the heart of the village. On the other hand, the subsequent deviation of the Marzenego river, which was brought to flow at Altino, made this waterway impracticable for trade, making the Salso Canal and its termination in the lagoon in the area called San Giuliano even more important. For this reason, trade moved from the northern part of Mestre to the southern part, contributing to the development of its new commercial center, around the Piazza Maggiore. From there also started a waterway (underground in the twenty-first century) called "Brenta vecchia" which ran through today's via Brenta vecchia, Dante, Fratelli Bandiera, and flowed into the Brenta canal in Malcontenta, and allowed boats to reach Padua from the center of Mestre . The increased strategic position of Mestre thus made it necessary to build a new fortress: the Castelnuovo, which was followed by a progressive abandonment of the Castelvecchio, which was finally demolished in the 15th century.

In 1452 a council was established to support the authority of the Venetian rectors in the administration of the village: in 1459 the council thus took its seat in the new Provvederia. In 1509, during the War of the League of Cambrai, the Venetian forces in retreat after the defeat in the battle of Agnadello, barricaded themselves under the command of Niccolò di Pitigliano in the castle of Mestre, which became the extreme bulwark on the mainland and from where the expeditions to the rescue of besieged Treviso, and to the reconquest of Padua, occupied by the Imperials. In 1513 Mestre, however, had to face again the assault of the Spaniards and Germans, who conquered the castle, sacking and burning the inhabited center. In honor of the heroic resistance, the city received the title of Mestre Fidelissima from the Serenissima, which is still its motto. In the eighteenth century the walls of Castelnuovo were demolished, now in a serious state of deterioration; of them only the Clock Tower and the twin Belfredo Tower remained.

With the fall of the Republic of Venice, Mestre was occupied by Napoleon Bonaparte's troops in May 1797, who put an end to the government of the last Venetian mayor and captain, Daniele Contarini. With the Treaty of Campoformio of 1797, the territories of the Republic of Venice passed to the Habsburgs of Austria. In 1805, following the Treaty of Presburgo, Veneto and Friuli became part of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy. Mestre, according to the French model, in 1806 became a "Municipality" within the Department of Tagliamento (the current province of Treviso), with a council of 40 members and a Podestà appointed by the central government. In 1808 it passed to the Department of the Adriatic (the current province of Venice) and in 1810 it absorbed the municipalities of Carpenedo, Trevignan and Favero. At the fall of Napoleon in 1814, Mestre returned under the dominion of the Habsburgs, within the Lombard-Veneto Kingdom. In 1842 the Milan-Venice railway was opened which, passing south of the town, shifted its center of gravity, with the development of via Cappuccina and Via Piave. On March 22, 1848, in the wake of the patriotic uprisings of the Risorgimento, while in Venice the insurgents led by Daniele Manin drove out the Austrians and proclaimed the Republic of San Marco, in Mestre the Civic Guard, established since the 18th, took control of the city.

Reinforced by soldiers, financiers and volunteers, it obtained the surrender of Forte Marghera and defended it against the Austrians who tried to reoccupy it. While the Austrians, pursued throughout the Lombardy-Veneto region, closed themselves up among the fortresses of the Quadrilatero, Mestre became a crossroads for the many volunteers who flocked from all over Italy. However, victorious against the Piedmontese troops and aimed at the reconquest of the entire Lombardy-Veneto region, on 18 June the Austrian troops entered Mestre again, reoccupying it and using it as a bridgehead for the siege of Venice. Despite the daring Sortie of Forte Marghera on 27 October which freed Mestre only for a few hours, on 26 May 1849 the Fort was reconquered by the Austrians, and the surrender of the fort was followed on 22 August by Venice itself. In 1866 Mestre saw the siege of Forte Marghera by Italian troops (which arrived in the city on July 15) and was annexed together with the rest of the Veneto to the Kingdom of Italy. On 6 March 1867 Giuseppe Garibaldi also arrived in Mestre, addressing the crowd from a balcony in Piazza Maggiore, an event later commemorated by a plaque.

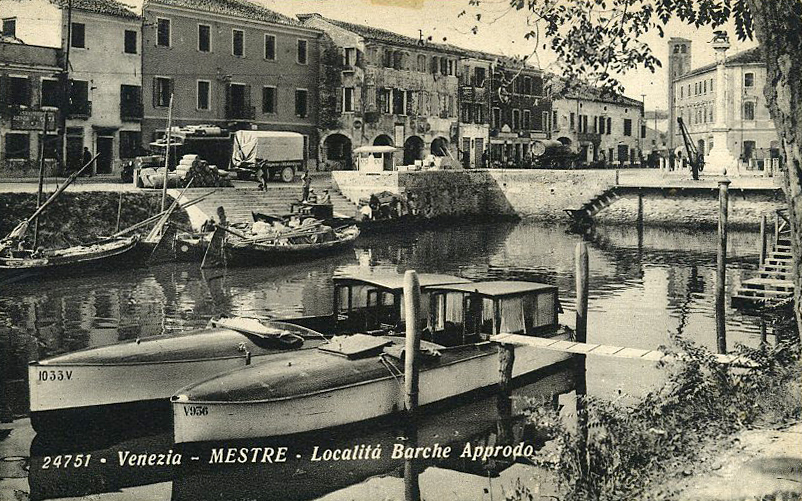

In 1876 the old Belfredo Tower, one of the last vestiges of the ancient castle, was demolished by the private individuals who owned it. There remains a trace of the plan of the tower, in the pavement of the homonymous street, adjacent to the "Giardini delle Mura" where the remains (as well as of a long stretch of wall) of one of the smaller towers of the castle are visible. In memory of the events of 1848, April 4, 1886 was inaugurated a commemorative column of the fallen in the resistance of 1848-1849 was inaugurated in Piazza Barche, while on November 13, 1898 the gold medal for military valor was awarded to the city. This motif of citizen pride has survived over time, and in the 2000s the "sortie of Mestre" was repeatedly recalled on various celebratory occasions. The mayors of Mestre 1866-1870: Girolamo Allegri 1871-1881: Napoleone Ticozzi 1882-1892: Pietro Berna 1892-1893: Agostino Tozzi 1894-1899: Pietro Berna 1899-1902: Jacopo Rossi 1903-1906: Giuseppe Frisotti 1907-1910: Pietro Berna 1910-1913: Aurelio Cavalieri 1914-1919: Carlo Allegri 1920-1922: Ugo Vallenari 1923: Gustavo Soranzo 1923-1924: Massimiliano Castellani 1924-1926: Paolino Piovesana It should also be remembered that on 1 May 1945, the day after the Liberation , the Allies set up a council of eight members in Mestre headed by the former mayor Vallenari, but it was dissolved about ten days later by the prefect Camillo Matter.

The referendums Starting from the end of the seventies, some committees cyclically proposed to the citizens of the referendums to ask for the separation of Venice from Mestre: between 1979 and 2003 there were four, two of which after only five years. The entire population of the municipality of Venice took part in the questions because the inhabitants of Mestre make up more than 10% of the total municipal population. All four referendums were unfavorable to the promoters of the separation, the first three due to a "No" victory, the fourth due to lack of a quorum. The first referendum with which the separation was attempted was held in 1979 and saw a participation of 79% of the voters of the municipality of Venice, with a percentage of in favor of separation equal to 27.7%; ten years later, in the referendum of June 25, 1989, the "Yes" to the separation increased in percentage, to 42.2%, even if the voters in the consultation were fewer, 74%. In February 1994, a little less than five years after the previous referendum, the question was re-proposed to the Venetians, and the turnout in the consultation dropped to 67%, even if the "Yes" percentage increased to 44.4%.

In November 2003 the fourth and, at present, most recent referendum, did not reach the minimum participation threshold: in fact only 39.3% of the voters went to the polls, making the question useless (to which, moreover, 65.3 % of voters answered "No"). This fourth defeat of the separatist front seems to have sanctioned the definitive end of the municipal split project; among the reasons of those who advocate an autonomous municipality are the impossibility for Venice to manage the many diversities of a territory that expands between square kilometers of land and lagoon and that favors the historic city center over the periphery; the antiscissionist front, on the other hand, argues that with the separation both centers, Venice and Mestre, alone would have had great difficulty in sustaining themselves, as the former progressively depopulated and aged, even though it was a tourist destination, while the latter would have ceased to be part of Venice for become an anonymous location.

In 1917, with a new law on ports, a quarter of the municipal territory of Mestre (Bottenigo, whose name has since been changed to Marghera) was integrated into the municipality of Venice and entrusted to the Società Porto Industriale di Venezia, which started the works that led to the creation of the first nucleus of Porto Marghera, initially called Porto di Mestre. In August 1926 (Royal Decree of 15 July 1926, no. 1317, in the Official Gazette no. 183 of 9 August 1926) the municipality of Mestre, which had 31,000 inhabitants and an area of ??12 km², was incorporated into the municipality of Venice, together with the municipalities Chirignago, Zelarino and Favaro Veneto. All this took place in the context of a general reorganization and rationalization of the municipal institutions which, throughout Italy, led to the unification of several municipalities.

In Venice, the act was also linked to the birth of the industrial center of Marghera, created by the economic policies of those years, centered around the activity of the industrial and politician Giuseppe Volpi count of Misurata and count Vittorio Cini. The Prime Minister, Minister of Finance and the Treasury, as well as president of the Porto Industriale di Venezia Society and of the Adriatic Electricity Society (then the main electricity industry in north-eastern Italy), strongly interested in a strong industrial development in the area; the second, president of the Adriatic Navigation Company, of SITACO interested in the construction of the new residential districts, as well as government commissioner for ILVA steelworks. Venice, due to its urban conformation, despite its wide availability of manpower, did not have suitable spaces to host its own modern industrial area: the expansion on the mainland became the necessary solution to give new development to the lagoon city.

On April 25, 1933, the Ponte Littorio was built (renamed Ponte della Libertà after the war) and with it the road section that led to today's highway to Padua. To connect it to Mestre, Corso Principe di Piemonte was traced (inaugurated in 1933, renamed Corso del Popolo after the war) and, to give more space to this road, a section of the Salso Canal was buried. During the Second World War Mestre underwent various aerial bombardments; the heaviest was that of March 28, 1944, which leveled more than a thousand houses, caused 164 deaths and 270 injuries, but also many displaced people who had to abandon their homes seeking hospitality in the surrounding countryside.

After the signing of the armistice, Mestre was the scene of clashes between the resistance forces and the Nazi-fascist forces who immediately tried to occupy it, also for its role as an important railway hub. In 1955, at the same time as the construction of Viale San Marco, the San Giuliano overpass was built, which thus made it possible to reach Venice directly without having to pass through Corso del Popolo. This overpass represents the final stretch of the state road to Trieste. Starting from the fifties, all the major urban centers of Italy underwent a rapid and disordered growth, which took place in their respective suburbs. Not even Venice escaped this phenomenon: the difference was that the Venetian capital, located in the center of a lagoon, did not have an external territorial belt that could act as a space for growth. Urban development therefore took place in the mainland areas and in particular in Mestre, which in a few years passed from a small country center of 20,000 inhabitants to a town of about 200,000 inhabitants, also thanks to the migratory flow from the historic center and the surrounding countryside.

Population growth increased further starting from the 1960s, when the disastrous effects of the 1966 flood, which showed the vulnerability of the houses on the lower floors of Venice, were added to the housing and work policies unfavorable to the lagoon residents. On the wave of emigration from the historic center, the maximum building and demographic expansion was reached in the seventies, a period in which Mestre and the mainland reached 210,000 inhabitants. The great speed of development, without a master plan, made it somewhat disordered, so much so that the phenomenon was defined by some circles as a lot of Mestre and the city was often pointed out as an example of an ungainly and not very pleasant urban center. The urban layout was upset, with radical changes in entire city areas and with the demolition of monuments and historical sites. Among the most impactful interventions, many of the canals of Mestre were drained, narrowed or diverted.

Even in the most central parts, such as in via Alessandro Poerio (the tombstone of the Marzenego), there was the construction of the Cel-Ana building leaning against the Tower, the first symbol of the city, the undergrounding of the Canal Salso from Piazza Ventisette Ottobre (the historic Piazza Barche, also shown in a famous painting by Canaletto), etc. Mestre thus became a heavily built city, boasting the national record of only 20 square centimeters of green per inhabitant (1980). The crisis of the chemical industry between the end of the eighties and the beginning of the nineties, together with the general downsizing of the large cities of northern Italy, led to a drop in the number of residents in Mestre and in the neighboring suburbs; nevertheless, the over 180,000 inhabitants of Mestre continue to make up over 66% of the population of the municipality of Venice.

Mestre

Address: Via Torre Belfredo

Phone: 041 2748111

Site:

www.comune.venezia.itLocation inserted by

Daniele Rubin